North to Boston

Life Histories from the Black Great Migration in New England

By Alison Barnet

Blake Gumprecht’s North to Boston, subtitled “Life Histories from the Black Great Migration in New England,” is a book of interviews with ten men and women who grew up in southern states and came to Boston in the 1950s and 1960s. (The years of the Great Migration are generally recognized as 1915 to 1970). Published this year, Gumprecht goes into great detail and pulls no punches. There is a lot to learn from this book.

Each personal story begins with a detailed description of the individual’s life in the South and ends with how their life was transformed in Boston. Gumprecht lets the interviewees speak out and say it like it is.

A few examples:

Geraldine W. was born in rural Clay County, Alabama. Her family was “very very poor”–so poor she had only two pairs of shoes, one for school and one for church. If Black people went into a store and a White customer came in after them, they had to step aside. In movie theatres, Blacks had to sit downstairs and Whites in the balcony. “They’d start throwing stuff on us,” said Geraldine. But her worst experience was being raped by an adult White boy in the house where she was a servant. When a sister already in Boston urged her to come and take a job as a live-in servant, Geraldine came to Boston in 1963. She says, “I felt like I came out of a cave. I’d never been out of the state.” At first, she “did not know how to act in such a different social environment. In a bus station, she once found herself looking around for the “colored” restroom. By the mid-1970s she had moved to Grant Manor on Washington Street, recalling by name all the nearby markets, restaurants, beauty salons, bars, and Skippy White’s Records.

Most people came to Boston because a relative already lived here. Only one of the ten interviewees had nobody here. Charles G. came from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, because he liked a jazz radio program allegedly broadcast from the South End’s Hi-Hat Club.

Ollie S. arrived in Boston in 1959 from Quitman, Mississippi, where Blacks had been prevented from voting for decades. Two of his siblings were already here and a third on the way. He believed “racism in Boston has diminished over time but still exists, even if it is expressed differently than in the South. “Down there they let you know that they’re racist,” he said. “Here they hide it. They don’t want you to know that they’re racist. They do it in a sneaky way. It wasn’t as great here as I thought it would be, but I learned to live with it.”

In the preface to North to Boston, Gumprecht writes, “When I began conducting interviews in 2015, I was immediately inspired by the lives of the migrants I met and realized the value of what I was doing.” Because many of the interviewees were quite old, “I feared that if someone didn’t record some of their stories before long, they would be lost forever.” He credits Rev. Gregory Groover of Roxbury, Mass’s Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal Church with reconnecting him with people he originally interviewed, their family and friends, as well as new migrants.

Gumprecht wrapped up with: “We seldom hear voices like these. The experiences of ordinary people teach us far more about America than any number of histories…These are people like us: Why wouldn’t you care about them?” and his last sentence is: “But their importance and the significance of the Great Migration in Boston are undeniable. Isn’t it time that Boston and Bostonians, particularly White Bostonians, acknowledged the contributions of its Black citizens to making the twenty-first-century city, especially Black people born in the South and their kin? It is past time. It’s overdue.”

Gumprecht, who now lives in El Paso, taught geography at universities in New Hampshire, South Carolina and Oklahoma for more than 20 years. He is the author of two previous books, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth and The American College Town, both of which won the American Association of Geographers’ J. B. Jackson Prize.

Alison Barnet is the author of five books, chiefly about the South End of Boston where she has lived since her college days in the 60s. This book review was first published in the Boston Sun.

********

Street Scenes: Oil Paintings

by Yetti Frenkel

Children with a Shopping Cart

Oil 28″ x 35″

I saw this group of children on Lynn Common. It struck me that adults are always dissatisfied with their lives while kids tend to live in the moment and enjoy what they have.

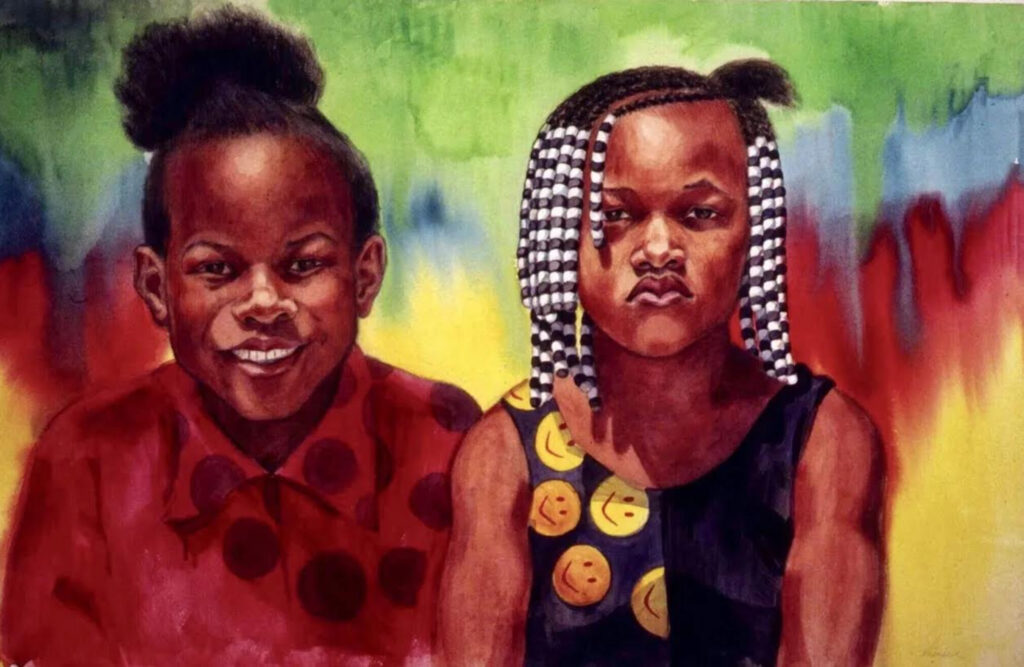

Sisters

Watercolor 27″ x 32″

I love the contrast between the girls. One is open and friendly, the other, wary. The unsmiling sister had just lost a front tooth and was concerned that her smile would reveal the gap.

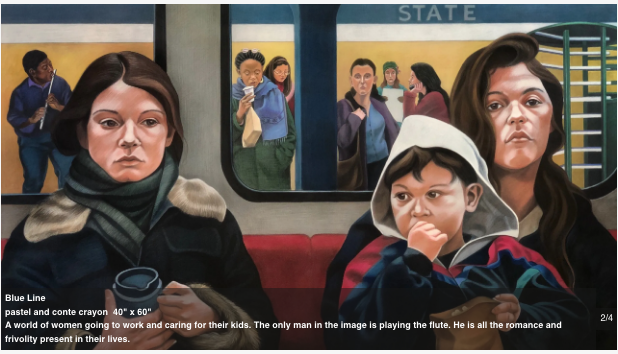

Blue Line

Pastel and conte crayon 40″ x 60″

A world of women going to work and caring for their kids. The only man in the image is playing the flute. He is all the romance and frivolity present in their lives.

Yetti—you capture the unique expressions on each face. Your portraits provide a sweet gaze into each individual. I especially appreciate your “Blue Line” portraits. I’ve been there. I’ve seen them. Claire