R. Crumb at the Grand Canyon , Swamp Willow, The Sounds Loneliness Makes

Poems by Claire Keyes

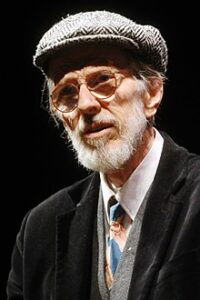

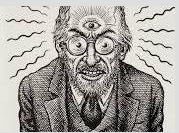

R. Crumb at the Grand Canyon

The Sounds Loneliness Makes

He comes out of the Men’s Room, short

and folded in on himself and I know him

by his scruffy dark beard, by the crush hat

he wears against the Arizona sun.

Like every cartoon of him you’ve ever seen, he’s pale.

Can you imagine R. Crumb sunning? Beside him,

his wife, the equally short and younger Aline,

adjusting her hair, wind-blown. Behind thick glasses,

his eyes scan the motley crowd of tourists

before he heads for the canyon, its fabulous crests

and stark plunges drawing the eye

a mile or more down to the copper-brown river.

Its brutality attracts him: some big ditch.

Brutal in his own way, he never flinches

from depicting his flaccid body and pocked face,

whiskers to scare children.

The canyon wears its scars with élan.

Over time they translate into beauty.

Beside it, celebrity is a moment’s interest,

then reduced, like everything else,

to a pip.

Not that he needed to tell us he was lonely.

Not that he wasn’t welcome to use the bedroom

that was my brother’s grown up, enlisted.

But those nights I’d lie awake

hearing Uncle Red’s footsteps as he climbed the stairs.

Was he drunk again? Then the thud of his shoes

as he dropped them, the fierce wooziness

of his snores.

Childless, he had been fatherly

when all we knew of father was distance. Giving

when all we knew was stricture. Summers,

he drove us to the beach, one arm on the wheel,

the other edging towards Aunt Jo’s knee, stopping

for the hair of the dog that bit him.

So I never said anything of my fear

that he would push open my door, fall on top of my bed.

Thinking, I don’t know what.

To protect him? To protect myself from saying?

Then he didn’t come home. One night, two:

found in an alley in the South End.

My father identified his body at the morgue.

No sounds

when he got home. Just the tightness of his jaw,

a look that said, Don’t ask.

Local Woman Missing, Locked Car Found on Shore Drive

Swamp Willow

She left no note, her shopping trip

ordinary as Egg Rock on the horizon.

Her husband escaped every morning, didn’t he?

And she pretended to sleep, delaying the change

from nightgown to street clothes:

what street, who to visit?

She watches a jogger

until he’s a spot on the beach.

She hasn’t run since she was a girl,

yet something pounds inside her.

She has no words for it,

but she’s never felt so present,

so entranced at the face that stares back

from the side window: a mouth

she can twist into a smile.

Rolling down the window, she sniffs

the rank odor of algae. It reminds her

of cabbages ripened and unpicked in their garden

among shallow‑rooted clover and celandine, weeds

she refused to pluck out. She takes pleasure in fruit

left to rot in the refrigerator beside leftovers

in plastic wrap, their blooms a luminous blue.

What dinner, who to feed? She slips off

her pumps, pulls on her son’s old running shoes.

He will search the towns to find her locked car

and never know why she was drawn to this shore.

She knew no one would notice: children

still in school, most runners tied up at noon.

And when she hardly casts a shadow,

she will run towards the water, slowly at first,

then stepping boldly onto the front page,

first a headline, then page two,

then a smudge on the fingers, an ache

that won’t go away.

Two men buttressed by a truck, a chipper attached

like a cranky caboose, take down the swamp willow.

Air-borne, one man wields his chain-saw

from a bucket dangerously close to utility wires.

The other feeds the tree, chunk by chunk

into the machine that chews them up

then shoots the chips into the maw of the truck.

The men work hard, cutting, lifting, shredding.

My willow won’t cradle the moon, nor shadow

the October yard, daisies spent, asters on the ascent.

After an hour’s hacking, the forked stump stands topless,

a remnant that opens up a space I’m not sure I can fill.

Once branches embraced the sky, roots stretched deep

into the past century.

The tree man commiserates, telling me

it was rotting away: ants, fungus.

Lose something every day, Elizabeth Bishop tells herself

as if she needed to practice, as if we could develop

a flair for loss.

After Giselle

In the crowded trolley, I feel someone touching me,

a man gesturing to the seat he’s vacated, asking,

Would you like to sit down?

His voice is hesitant and even though I’m stiff

from three hours folded into a balcony seat at the ballet,

I’d rather stand and take pleasure

in the swaying of the car and the vision of myself

performing an arabesque, my right leg elevated,

toe pointed back

while my left leg steadies and supports the line of my body

parallel to the floor.

For my back is limber, had better be

after all my sun salutations, my vinyasas.

And here’s this man.

The look in his eyes, like I’m his beloved granny.

Is he twenty, twenty-five?

He sees not a prima ballerina, but a woman of a certain age.

I’d like to slug him, blacken his clueless eyes.

Still, there’s his gallantry, rare as Raleigh’s cape

here in Boston on the Green Line early in the 21st century.

So I thank him and sit down.

All Claire Keyes’ poems above are taken from What Diamonds Can Do, Cherry Grove Collections, 2015 available from ABE Books.com